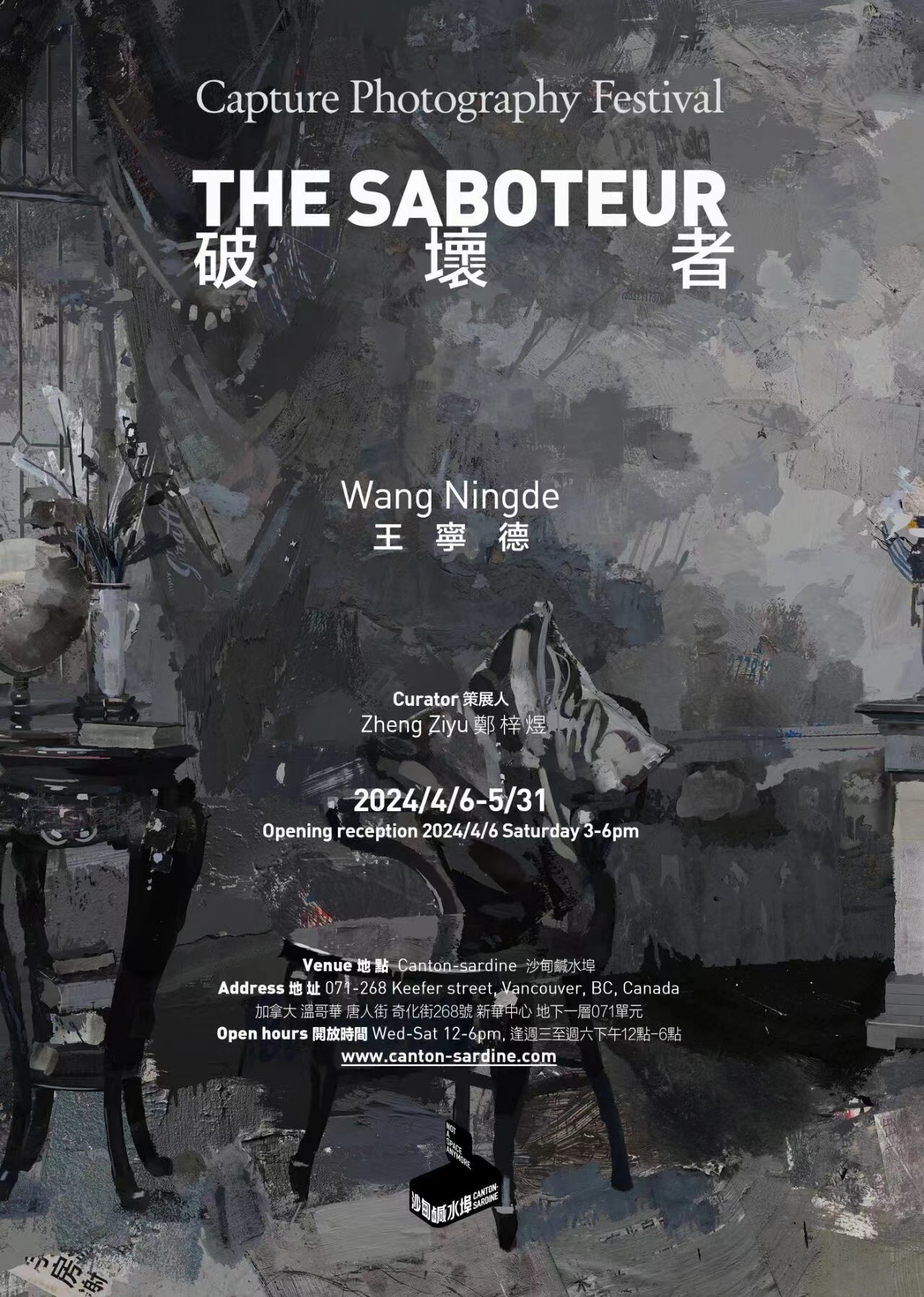

The Saboteur

April marks the return of Capture Photography Festival, the largest photography art festival on Canada's West Coast. The organizers form a jury composed of the most influential critics, curators, and scholars in Canada to decide on the most representative photography exhibitions in the Greater Vancouver area as official selected exhibitions. This year, Wang Ningde's solo exhibition at Canton-sardine space was selected for the festival's official exhibition. This marks the first time Wang Ningde's photographic works are showcased in Canada through a solo exhibition. The exhibition is curated by Mr. Zheng Ziyu, an associate professor at Sun Yat-sen University. The exhibition will open on April 6th from 3 PM to 6 PM in Vancouver.

Zhou Yaochu's Photography Studio, 170 x 150 cm, pigment inkjet print on archival acid free cotton paper, ©️ Wang Ningde, 2024

For this solo exhibition in Vancouver, Wang Ningde specially created a brand-new work. The artist delved deeply into the historical and cultural context of Vancouver, conducting extensive research and analysis to produce a piece closely connected to the history of Vancouver’s Chinatown—the location of the exhibiting gallery.

Zhou Yaochu was the first Chinese photographer in Vancouver in the early 20th century. Born on June 3, 1876, in Kaiping, Guangdong Province, China, he arrived in Canada in 1902. By 1906, he had saved enough money to purchase equipment and opened a studio at 68 West Hastings Street. When Zhou Yaochu arrived and began his photography business, profound racial divisions existed in Canada and the Lower Mainland of British Columbia. Anti-Asian racism permeated all aspects of life, including employment, housing, education, and civic participation. From September 7 to 9, 1907, following a parade organized by the Anti-Asian League advocating for the prohibition of Asian immigration, a mob attacked residents and businesses in Vancouver’s Chinatown and Japantown. This is the atmosphere in which Zhou Yaochu’s studio operated.

In the 1900s, white tailors and barbers refused to serve the Sikh community, but Zhou Yaochu welcomed members of the Sikh community to his studio. Under the same backdrop, he also photographed Black people, Chinese, Hindus, Indigenous peoples, and new immigrants from Eastern Europe such as Ukrainians and Poles.

In this studio, Zhou Yaochu, with his diligence and pragmatism, served everyone—celebrities, the wealthy, and the poor alike. People were not turned away because of their skin color, social status, or beliefs. As a result, his work reveals the diverse faces of Vancouver’s unique past. Community historian Catherine Clement discovered Zhou Yaochu’s surviving photographs and spent a decade recovering part of his lost works. This effort led to an exhibition and the publication of a book in 2019 titled Chinatown Through a Wide Lens: The Hidden Photographs of Yucho Chow.

When artist Wang Ningde received the invitation for the exhibition, it coincided with the 100th anniversary of the implementation of Canada’s Chinese Immigration Act, also known as the "Chinese Exclusion Act." Drawing on these surviving photographs, Wang Ningde, himself a photographer, recreated one of the backdrops from Zhou Yaochu’s studio. As mentioned earlier, people of different races and faiths once stood here. In the moment illuminated by the flash, they set aside divisions and hostilities, striving only to present their best selves—a stark contrast to the realities and atmosphere on the streets of that era. Using his own creative methods, Wang Ningde depicted this illusory microcosm, paying tribute through this work to Zhou Yaochu and the spirit of inclusivity and peace he represented.

Dr. Zheng Ziyu, the curator of this exhibition, remarked: “Through a mending of imagination based on fragments of historical imagery, Wang Ningde has restored the space of a once-renowned Chinese photography studio in Vancouver. Every prop and detail in this work has appeared more than once in the family albums of people of different races, skin colors, and social classes. This seemingly real yet illusory scene is like the skeleton of history clothed in the flesh of the present—empty and silent, yet concealing memories of Canada’s past racial exclusion and the struggle for survival on the margins.”